Remote Control¶

Brutal Maze provides a INET (i.e. IPv4), STREAM (i.e. TCP) socket server which

can be enabled in the config file or by adding the --server CLI flag.

After binding to the given host and port, it will wait for a client to connect.

Then, in each cycle of the loop, the server will send current details of

each object (hero, walls, enemies and bullets), wait for the client to process

the data and return instruction for the hero to follow. Since there is no EOT

(End of Transfer) on a socket, messages sent and received between server

and client must must be strictly formatted as explained below.

Server Output¶

First, the game will export its data to a byte sequence (which in this case, is simply a ASCII string without null-termination) of the length \(l\). Before sending the data to the client, the server would send the number \(l\) padded to 7 digits.

Below is the meta structure of the data:

<Map height (nh)> <Number of enemies (ne)> <Number of bullets (nb)> <Score>

<nh lines describing visible part of the maze>

<One line describing the hero>

<ne lines describing ne enemies>

<nb lines describing nb bullets>

The Maze¶

Visible parts of the maze with the width \(n_w\) and the height \(n_h\) are exported as a byte map of \(n_h\) lines and \(n_w\) columns. Any character other than 0 represents a blocking cell, i.e. a wall.

To avoid floating point number in later description of other objects, each cell has the width (and height) of 100, which means the top left corner of the top left cell has the coordinates of \((0, 0)\) and the bottom right vertex of the bottom right cell has the coordinates of \((100 n_w, 100 n_h)\).

The Hero¶

6 properties of the hero are exported in one line, separated by 1 space, in the following order:

- Color:

The current HP of the hero, as shown in in the later section.

- X-coordinate:

An integer within \([0, 100 n_w]\).

- Y-coordinate:

An integer within \([0, 100 n_h]\). Note that the y-axis points up-side-down instead of pointing upward.

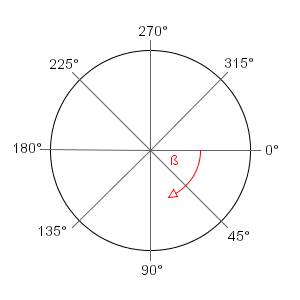

- Angle:

The direction the hero is pointing to in degrees, cast to an integer from 0 to 360. Same note as above (the unit circle figure might help you understand this easier).

- Can attack:

0 for no and 1 for yes.

- Can heal:

0 for no and 1 for yes.

The Enemies¶

Each enemy exports these properties:

- Color:

The type and the current HP of the enemy, as shown in the table below.

- X-coordinate:

An integer within \([0, 100 n_w]\).

- Y-coordinate:

An integer within \([0, 100 n_h]\).

- Angle:

The direction the enemy is pointing to in degrees, cast to a nonnegative integer.

To shorten the data, each color (in the Tango palette) is encoded to a lowercase letter. Different shades of a same color indicating different HP of the characters.

HP |

5 |

4 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Butter |

|

|

|

||

Orange |

|

|

|

||

Chocolate |

|

|

|

||

Chameleon |

|

|

|

||

Sky Blue |

|

|

|

||

Plum |

|

|

|

||

Scarlet Red |

|

|

|

||

Aluminium |

|

|

|

|

|

Note

If a character shows up with color 0, it is safe to ignore it

since it is a dead body yet to be cleaned up.

Flying bullets¶

Bullets also export 4 properties like enemies:

- Color:

The type and potential damage of the bullet (from 0.0 to 1.0), encoded similarly to characters’, except that aluminium bullets only have 4 colors

v,w,xand0.- X-coordinate:

An integer within \([0, 100 n_w]\).

- Y-coordinate:

An integer within \([0, 100 n_h]\).

- Angle:

The bullet’s flying direction in degrees, cast to a nonnegative integer.

Example¶

Above snapshot of the game is exported as:

19 5 3 180

00000000000000000vvvv0000

v0000000000000000vvvv0000

v0000000000000000vvvv0000

v0000000000000000vvvv0000

vvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvv0000

vvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvv000v

vvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvv000v

vvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvv00000

0000000000000000000000000

0000000000000000000000000

0000000000000000000000000

v000000000000000000000000

v000000000000000000000000

v000000000000000000000000

v000vvvvvvv000vvv0vvv0000

v000vvvvvvv000vvvvvvv0000

v000vvvvvvv000vvvvvvv0000

v000vvvvvvv000vvvvvvv0000

v000000vvvv000000vvvv0000

v 1267 975 47 0 1

p 1817 1050 45

g 1550 1217 45

a 2250 1194 45

p 2050 1017 45

e 1850 950 358

x 2126 1189 361

e 1541 1020 167

v 1356 1075 49

Client Output Format¶

Every loop, the server receives no more than 7 bytes in the format of

<Movement> <Angle> <Attack>. Again, these values need to be

specially encoded.

Movement¶

This is the most awkward one. As we can all imagine, there are nine different

directions for the hero to move. Were they represented as two-dimensional

vectors, at least three characters would be needed to describe such

a simple thing, e.g. 1 0 for \(m = (1, 0)\), and in the worst-case

scenario \(m = (-1, -1)\), we would need five: -1 -1. 40 bits are used

to carry a four-bit piece of data, freaking insane, right? So instead,

we decided to slightly encode it like this:

Direction |

Left |

Nil |

Right |

|---|---|---|---|

Up |

0 |

1 |

2 |

Nil |

3 |

4 |

5 |

Down |

6 |

7 |

8 |

Angle¶

Direction to point to hero to, might be useful to aim or to perform a close-range attack manually. This value should also be converted to degrees and casted to a nonnegative integer.

Attack¶

Attack can be either of the three values:

Do nothing

Long-range attack

Close-range attack

Simple, huh? Though be aware that this won’t have any effect if the hero can yet strike an attack (as described in above section about The Hero).

Pseudo-Client¶

Create an INET, STREAMing socket

sockConnect

sockto the addresshost:portwhich the server is bound toReceive length \(l\) of data

If \(l > 0\), close

sockand quitReceive the data

Process the data

Send instruction for the hero to the server and go back to step 3

Your AI should try to not only reach the highest score possible, but also in the smallest amount of time. For convenience purpose, the server will log these values to stdout.

There are samples of client implementations in different languages in the client-examples directory (more are coming).